Extent of involvement in social rehabilitation among obstetric fistula patients at Kitovu Hospital, Uganda

Shallon Atuhaire1*, Akin-Tunde A. Odukogbe2, John F. Mugisha3, Oladosu A. Ojengbede

1Pan African University of Life and Earth Sciences Institute, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan / University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria

3Cavendish University, Kampala, Uganda

Abstract

Introduction: Obstetric fistula is highly debilitating with effects acknowledged as beyond treatment thus, it requires physical and social rehabilitation. The study described the extent to which obstetric fistula patients have been involved in social rehabilitation services at Kitovu Hospital in Uganda.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey that used mixed methods was done among 390 obstetric fistula patients and 12 key informants at Kitovu Hospital in Uganda. The 390 patients responded to a semi-structured questionnaire, and 10 of them were involved in in-depth interviews. The 12 key informants were hospital staffs actively involved in the management of obstetric fistula, and patients’ partners who were involved in care giving. The variables under investigation included: socio-demographic and obstetric factors alongside whether the patients had been empowered, earned daily, had received aid to startup an income generating activity, had skills training, counseling, physiotherapy, health education, needs assessment and whether their needs had been addressed.

Results: Among the 390 participants, 192 (49.2%) had had fistula repair, 198 (50.8%) had not had repair, 215 participants felt they had not been empowered at all, 215 did not earn daily. Again, 211 indicated that they had not received aid to startup an income generating activity, 235 had not received skills training, 195 had not received counseling, and 299 had not had physiotherapy. A significant difference was noted across all the variables (empowerment, daily earning, having received aid to startup an income generating activity, skills training, counseling, physiotherapy, health education, needs assessment and having their needs addressed) and their repair category with a P-value of <0.001. Qualitative findings also indicated that patients received inadequate social rehabilitation due to inadequate resources. Patients preferred fistula repair before they could be socially rehabilitated as they still felt incapacitated.

Conclusions: A larger proportion of patients with unrepaired fistula had not been involved in social rehabilitation compared to those whose fistula had been repaired. More repair and rehabilitation centers ought to be constructed and adequately facilitated for the patients to receive the services they desire for effective social rehabilitation.

Introduction

Obstetric fistula is a debilitating condition, yet among marginalized women, least visible with unheard voices. The continual leakage of urine, in some instances feces or both and the accompanying offensive smells deter the fulfillment of their roles and goals.1 Patients are ostracized and abandoned hence they struggle for their own survival.2 Conservatively, it is estimated that 2 million women are living with obstetric fistula globally, almost all of them are situated in the Arab region, Africa and Southeast Asia.3 The number is predictably higher given the stigma, and misconceptions associated which limit voluntary disclosure by the patients4 and also the deficiency of Health Management and Information System (HMIS) which does not easily track the patients.5 Besides, surgical repair is often delayed due to a limited number of specialized surgeons and costs involved. According to Baker et al, (2015), the average cost is US $ 450. This is mainly dependent on the length of hospital stay and complexity of the fistula.6

The repair of the fistula is fundamentally possible and has a success rate of over 80% especially if it is an uncomplicated form7 but generally, it ranges between 65 - 90%.8 Governments across the African region have devised and are implementing strategies to end fistula.1,9. The Republic of Uganda is working closely with other stakeholders in implementing the National Obstetric Fistula Strategy (NOFS), 2011/2012-2015/2016. The focus is on mass campaigns and medical camps where repair and rehabilitation services are offered. For example, in 2015 about 2560 repairs were done in Uganda.10 The centers involved are Mulago National Referral, Mbale, Hoima, Fort Portal, Mbarara, Kabale, Soroti, Moroto, Masaka, Lira, Jinja, Arua and Gulu which are regional referrals and Kagando, Lacor, Kamuli, Kumi, Kitovu, Kisiizi, and Virika which are all mission hospitals.11 Kitovu Hospital has the highest obstetric fistula repair rates in the country and globally.12 Nonetheless, the backlog and the incidence rates remain high due to the limited number of surgeons, and the deficiency in the health care system.10,11

Treatment centers and studies acknowledge the need for social rehabilitation as patients decline to leave when they are discharged after repair,2 also when patients continue to present with health concerns.5 Social rehabilitation includes training or experiences aimed to empower and advance the quality of women’s lives before or after corrective surgery.1,9 Most treatment facilities have rehabilitation centers and are in partnership with community based organizations specializing in social rehabilitation services where patients are trained in vast activities as life skills, craft making, tie and dye, embroidery, knitting, hair dressing and literacy. During this time, they are also counseled.1,2,9 The skills obtained do not benefit the patients alone but the entire family and community.13 When social rehabilitation especially counseling is initiated earlier, it quickens the overall healing process.9 The organizations internationally involved are: Fistula Care Plus,14 World Health Organization, Women and Development against Distress in Africa, International Organization for Women and Development. African Medical Research Foundation (AMREF), United Nations Population Fund(UNFPA), EngenderHealth, and the Foundation for Women’s Health Research and Development (FORWARD). Those operating locally in Uganda are: The Association for Rehabilitation and Re-Orientation of Women for Development (TERREWODE), Uganda Village Project, Comprehensive Rehabilitation Services in Uganda (CoRSU) and the Women and Development against Distress in Africa (WADADIA).15 These carry out assessment of the patients, their homes and prepare them for social reintegration and rehabilitation.9 But, there is comparatively scanty information on the extent to which obstetric fistula patients in different repair categories have been involved in social rehabilitation at Kitovu Hospital in Uganda which compelled this study. The findings of this study could be utilized to plan for effective social rehabilitation of obstetric fistula patients.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

A cross-sectional retrospective inquiry of how obstetric fistula patients had been involved in social rehabilitation was done. A mixed research methods approach that admitted a semi-structured questionnaire, key informant and, in-depth interview guides were used to collect and analyze data among obstetric patients that had been registered by Kitovu Hospital, Masaka, Uganda during the period of two years before data collection. The center has a specialized unit for the management of obstetric fistula.

Study population

The study participants included the hospital staff actively involved in the management of obstetric fistula. These included: program director, obstetric fistula surgeons, nurses, social workers, desk officers, obstetric fistula patients and their partners.

Sample size

A total of 390 participants were involved in quantitative methodology while 22 were involved in qualitative methodology. Only obstetric fistula patients in different repair categories were involved in quantitative methods for a period of six months from March 2019 to the end of August, 2019 during the various annual camps at Kitovu Hospital. The sample size was calculated using a formula for comparison of proportion.16 During the calculation of sample size, 50% were the assumed percentage of higher self-efficacy among patients whose fistula has been repaired and 35% was the assumed percentage of higher self-efficacy among patients whose fistula has not been repaired. The remaining 15% catered for non-responses. Therefore, the sample size was 390 among whom 195 participants should have had a fistula repair and 195 should have not yet had fistula repair.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

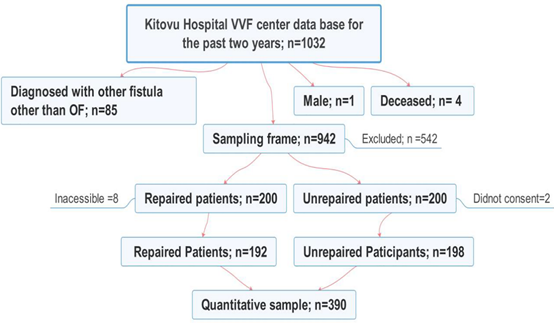

The key informants were included due to their involvement in the management of obstetric fistula. Those not directly involved were excluded. A total of 1032 gynecological fistula patients had been registered by Kitovu Hospital for two years through the time of data collection. Patients who had been registered by the hospital earlier were excluded. Of 1032, only 942 (91.3%) had obstetric fistula. Their biodata was entered in SPSS 25.0 and a simple random sampling command was run to select 400 (42%) patients (200 of them having had fistula repair and 200 awaiting repair). Of the patients who had had fistula repair (200), 8 (4%) were inaccessible and 2 (1%) of those who had not yet had repair did not consent. Hence, only 192 patients whose fistula had been repaired and 198 patients whose fistula had not yet been repaired participated in the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria has been schematised as in figure 1.

Figure 1: Flowchart showing the sampling procedure for quantitative methodology

Data collection tools

These included key informant, in-depth interviews, and a semi-structured questionnaire. The use of key informant, and in-depth interview guides were illustrated as in Table 1. The tools were edited and translated into Luganda and Kiswahili languages being the widely spoken in the region. The research assistants were trained.

Table 1: Use of qualitative methods data collection tools

|

Interview |

Who? |

Number |

Time (Minutes) |

|

Key Informant |

specialists, nurses, desk officer, social workers, partners |

12 |

60 |

|

In-depth |

Patients |

10 |

30 |

Semi-structured questionnaire

Carpenter, J. et al (2003)’s five Likert scale was used to measure social rehabilitation.17 The scale ranged from “Very highly” rated at 5, “Highly” at 4, “Moderately” at 3, “Low” at 2 and “Not at all” at 1. Repair status was categorised as repaired or unrepaired.

Qualitative data management and analysis

The recordings and field notes taken during interviews were listened to and read over to have an overall impression of the participants’ ideas. ATLAS.ti version 7.5, a computer software for analyzing qualitative data, was used to code and systematically identify related themes.

Quantitative data management and analysis

Quantitative data was entered in a Special Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) 25.0., coded, cleaned and analyzed using the same software. Pearson’s Chi square correlations were used to measure the extent of involvement in social rehabilitation among the obstetric fistula patients.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Higher Degrees, Research and Ethics Committee, Makerere University School of Public Health under protocol number 639 and also from the National Council for Science and Technology (NCST) under IRB number HS361ES.

Results

Socio-demographic and obstetric factors among obstetric fistula patients

The study was done among 390 obstetric fistula patients among whom 58 (14.9%) were eighteen years old and below, 183 (47.0%) between nineteen to twenty nine years, and the rest were above 30 years. A greater number of patients, 333 (85.4%) had primary level of education while the rest had secondary and above. Concerning marital status, 178 (45.6) had been divorced, 117 (30%) were married, 78 (20%) were single, and 17 (4.4%) were widows. A large number of patients 205 (52.6%) came from central region while the rest were distributed across other regions.

Regarding obstetric factors, 192 (49.2%) had had fistula repair, while 198 (50.8%) had not yet had fistula repair. Of those whose fistula had been repaired, 158 (82.3%) were successful whereas 34 (17.7%) were unsuccessful. The sociodemographic and obstetric factors were represented in Table 2.

Table 2: Sociodemographic and obstetric factors of obstetric fistula patients

|

Variable |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Age |

|

|

|

Mean ± SD |

30.27±13.35 |

|

|

Median |

27.00 |

|

|

≤ 18 years old |

58 |

14.9 |

|

19 -29 years old |

183 |

47.0 |

|

30 - 39 years old |

69 |

17.7 |

|

40 -49 years old |

42 |

10.8 |

|

50 years and above |

37 |

9.5 |

|

Total |

389 |

100 |

|

Level of Education |

|

|

|

Primary and Below |

333 |

85.4 |

|

Secondary |

51 |

13.1 |

|

Tertiary |

6 |

1.5 |

|

Total |

390 |

100.0 |

|

Marital Status |

|

|

|

Single |

78 |

20.0 |

|

Married |

117 |

30.0 |

|

Separated/Divorced |

178 |

45.6 |

|

Widowed |

17 |

4.4 |

|

Total |

390 |

100.0 |

|

Region |

|

|

|

Central |

205 |

52.6 |

|

Eastern |

85 |

21.8 |

|

Northern |

40 |

10.3 |

|

Western |

60 |

15.4 |

|

Total |

390 |

100.0 |

|

Obstetric fistula repair category |

|

|

|

Repaired |

192 |

49.2 |

|

Unrepaired |

198 |

50.8 |

|

Total |

390 |

100.0 |

|

Outcome of repair if ever repaired |

|

|

|

Successful |

158 |

82.3 |

|

Unsuccessful |

34 |

17.7 |

|

Total |

192 |

100.0 |

Extent of involvement in social rehabilitation among obstetric fistula patients

The attributes of social rehabilitation measured were whether patients had been empowered to take part in decision making, their daily earnings, whether they had been aided to startup an income generating activity, had skills training, been counseled, had physiotherapy, health education, had their needs assessed, and met. Their responses included: not at all, low level, moderately, highly, and very highly. The frequencies of their responses were represented in Table 3. Of the 390 participants, 215 (55.1%) had not been empowered to take part in decision making at all, 112 (28.7%) had been empowered at a low level, 55 (14.1%) had been moderately empowered, 6 (1.5%) highly empowered while 2 (0.5%) had been very highly empowered to take part in decision making.

Table 3: Frequency of involvement in social rehabilitation among obstetric fistula patients

|

Variable |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

I have been empowered to take part in decision making |

|

|

|

Not at all |

215 |

55.1 |

|

Low level |

112 |

28.7 |

|

Moderately |

55 |

14.1 |

|

Highly |

6 |

1.5 |

|

Very highly |

2 |

0.5 |

|

Total |

390 |

100.0 |

|

I earn daily |

|

|

|

Not at all |

222 |

57.2 |

|

Low level |

109 |

28.1 |

|

Moderately |

50 |

12.9 |

|

Highly |

6 |

1.5 |

|

Very highly |

1 |

0.3 |

|

Total |

388 |

100.0 |

|

I have been aided to start up an income generating activity |

|

|

|

Not at all |

210 |

54.1 |

|

Low level |

107 |

27.6 |

|

Moderately |

57 |

14.7 |

|

Highly |

12 |

3.1 |

|

Very highly |

2 |

0.5 |

|

Total |

388 |

100.0 |

|

I have had skills training |

|

|

|

Not at all |

235 |

60.4 |

|

Low level |

56 |

14.4 |

|

Moderately |

69 |

17.7 |

|

Highly |

22 |

5.7 |

|

Very highly |

7 |

1.8 |

|

Total |

389 |

100.0 |

|

I have been counseled |

|

|

|

Not at all |

195 |

50.1 |

|

Low level |

76 |

19.5 |

|

Moderately |

47 |

12.1 |

|

Highly |

48 |

12.3 |

|

Very highly |

23 |

5.9 |

|

Total |

389 |

100.0 |

|

I have had physiotherapy |

|

|

|

Not at all |

299 |

77.1 |

|

Low level |

56 |

14.4 |

|

Moderately |

24 |

6.2 |

|

Highly |

8 |

2.1 |

|

Very highly |

1 |

0.3 |

|

Total |

388 |

100.0 |

|

I have had health education about obstetric fistula |

|

|

|

Not at all |

198 |

50.9 |

|

Low level |

52 |

13.4 |

|

Moderately |

54 |

13.9 |

|

Highly |

56 |

14.4 |

|

Very highly |

29 |

7.5 |

|

Total |

389 |

100.0 |

|

My needs have been assessed |

|

|

|

Not at all |

296 |

75.9 |

|

Low level |

62 |

15.9 |

|

Moderately |

23 |

5.9 |

|

Highly |

6 |

1.5 |

|

Very highly |

3 |

0.8 |

|

Total |

390 |

100.0 |

|

My needs have been taken care of |

|

|

|

Not at all |

325 |

83.8 |

|

Low level |

37 |

9.5 |

|

Moderately |

20 |

5.2 |

|

Highly |

4 |

1.0 |

|

Very highly |

2 |

0.5 |

|

Total |

388 |

100.0 |

According to the qualitative findings of in-depth interviews, 10 patients participated, six of whom had not had repair while 4 had had repair with two of them being unsuccessful. Those who had not had repair and those whose repair had been unsuccessful expressed that they had not involved in decision making at all. When asked "Can you influence decision in your family?” the following responses were given: “Not at all. I am never informed of anything and so I do not take part in decision-making”, P 1: Case 1 - 1:22, unrepaired, aged 20. Another one added, “No, we are two worlds apart. They do not hear from me. I do not hear from them”, P 2: Case 2 - 2:22, unsuccessfully repaired, age 28. “No, I am not involved in any activity at home not even in decision-making. I do not know what is happening because I am cutoff”, P 3: Case 3 - 3:22, unrepaired, aged 25. Similarly was another unsuccessfully repaired patient aged 34, who said, “No, they do not inquire from me anymore. I do not know what they are planning, I just see things happening”, P10: Case 10 - 10:22. Some of the patients who had had successful repair had been rehabilitated and reintegrated, hence were involved in decision making. One of the successfully repaired who was 21 years old said, “Yes I do, everyone in my family is asked for an opinion about a given situation before our mother can make decision”, P 9: Case 9 - 9:22.

Concerning daily earning, 388 participants responded, of these 222 (57.2%) did not earn at all, 109 (28.1%) earned but at a low level, 55 (12.9%) earned moderately, 6 (1.5%) earned highly, while 2 (0.5%) were earning very highly.

Concerning whether they had been aided to startup an income generating activity, 388 participants responded, of these 210 (54.1%) had not received any aid at all, 107 (27.6%) had but at a low level, 57 (14.7%) had moderately received some aid, 12 (3.1%) had highly received aid, while only 2 (0.5%) had very highly received aid.

With regards to skills training, 389 participants responded, of these 235 (60.4%) had not had skills training at all, 56 (14.4%) had but at a low level, 69 (17.7%) had moderately skills training, 22 (5.7%) had highly been trained, while 7 (1.8%) had very highly been trained. In relation to this, interviews with patients yielded the following results: “I need to recover first and then be supported through skills training and financial aid”, P 1: Case 1 - 1:32, unrepaired, aged 20. “I need repair first because being skilled in this condition is useless. For example, I can weave baskets and mats but I cannot take them to the market”, P 2: Case 2 - 2:32, unsuccessfully repaired, aged 28. “I have skills; my family taught me many skills but I am unable to execute them now. I need support in seeking treatment; I also need to better my skills because I am not perfect in what I am able to do”, P 3: Case 3 - 3:32, unrepaired, aged 25. “Yes, skills are important but they can be applied when one has been repaired. I need medical support first and then my community should be sensitized about this condition”. P 7: Case 7 - 7:32, unrepaired, aged 16.

Patients who had had successful repair of the fistula also expressed need for more skills training as resources had been inadequate for them to be competent. They reported, “I still need support. I was trained in tailoring at the hospital but I am not yet competent, and I need a personal machine”, P 4: Case 4 - 4:32, repaired, 29 years of age. “Yes, having multiple skills such as entrepreneurship, financial management, hair dressing, fashion design and public relations has enable me to reconnect with my former customers and attract new ones”. P 8: Case 8 - 8:32, repaired, aged 31. “My ability to perform various activities is enough to enable reintegrate, however I need more knowledge, skills and demonstrations on best farming practices”, P 9: Case 9 - 9:32, repaired, aged 21.

About counseling, 389 participants responded, of these 195 (50.1%) had not received counseling at all, 76 (19.5%) had but at a low level, 47 (12.1%) had moderately received counseling, 48 (12.3%) were highly counseled, while 23 (5.9%) had been very highly counseled. Concerning physiotherapy, 388 participants responded, of these 299 (77.1%) had not had physiotherapy at all, 56 (14.4%) had but at a low level, 24 (6.2%) had moderately had physiotherapy, 8 (2.1%) had highly been involved in physiotherapy, while 1(0.3%) had been very highly engaged in physiotherapy. With regards to health education, 389 respondents answered, of these 198 (50.9%) had not received any health education at all, 52 (13.4%) had but at a low level, 54 (13.9%) had moderately had health education, 56 (14.4%) had been highly educated while 29 (7.5%) had been very highly educated about obstetric fistula.

About needs assessment, a total of 398 participants responded, of these 296 (75.6%) had not had their needs assessed at all, 62 (15.9%) had but at a low level, 23 (12.1%) had had their needs moderately assessed, 6 (1.5%) had had their needs highly assessed, while 3(0.8%) had had their needs very highly assessed. At the same time, patients were asked if their needs had been addressed. Of the 388 patients who responded, 325 (83.8%) had not had their needs addressed at all, 37 (9.5%) said their needs had been addressed but at a low level, 20 (5.2%) had had their needs addressed moderately, 4 (1.0%) had had their needs highly addressed, while 2 (0.5%) had had their needs very highly taken care of.

The results from the bivariate analysis of the extent of participation in social rehabilitation represented in Table 4 revealed a significant difference between the patients in different fistula repair categories.

Table 4: Bivariate analysis of the extent of participation in social rehabilitation among obstetric fistula patients of different repair status

|

Variable |

Obstetric fistula repair status |

Total |

X2 |

P-value |

|

|

|

Repaired (%) |

Unrepaired (%) |

|

|

|

|

I have been empowered to take part in decision making |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all |

83(38.6) |

132(61.4) |

215 |

22.856 |

<0.001 |

|

Low level |

69(61.6) |

43(38.4) |

112 |

||

|

Moderately |

34(61.8) |

21(38.2) |

55 |

||

|

Highly |

4(66.7) |

2(33.3) |

6 |

||

|

Very highly |

2(100.0) |

0(0.0) |

2 |

||

|

Total |

192(49.2) |

198(50.8) |

390 |

|

|

|

I earn daily |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all |

79(35.6) |

143(64.4) |

222 |

40.025 |

<0.001 |

|

Low level |

71(65.1) |

38(34.9) |

109 |

||

|

Moderately |

35(70.0) |

15(30.0) |

50 |

||

|

Highly |

5(83.3) |

1(16.7) |

6 |

||

|

Very highly |

1(100.0) |

0(0.0) |

1 |

||

|

Total |

191(49.2) |

197(50.8) |

388 |

|

|

|

I have been aided to start up income generating activity or project |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all |

72(34.3) |

138(65.7) |

210 |

46.903 |

<0.001 |

|

Low level |

65(60.7) |

42(39.3) |

107 |

||

|

Moderately |

41(71.9) |

16(28.1) |

57 |

||

|

Highly |

11(91.7) |

1(8.3) |

12 |

||

|

Very highly |

2(100.0) |

0(0.0) |

2 |

||

|

Total |

191(49.2) |

197(50.8) |

388 |

|

|

|

Have you been trained in any skills |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all |

79(33.6) |

156(66.4) |

235 |

60.364 |

<0.001 |

|

Low level |

38(67.9) |

18(32.1) |

56 |

||

|

Moderately |

49(71.0) |

20(29.0) |

69 |

||

|

Highly |

18(81.8) |

4(18.2) |

22 |

||

|

Very highly |

7(100.0) |

0(0.0) |

7 |

||

|

Total |

191(49.1) |

198(50.9) |

389 |

|

|

|

I have been counseled |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all |

30(15.4) |

165(84.6) |

195 |

192.135 |

<0.001 |

|

Low level |

52(68.4) |

24(31.6) |

76 |

||

|

Moderately |

43(91.5) |

4(8.5) |

47 |

||

|

Highly |

46(95.8) |

2(4.2) |

48 |

||

|

Very highly |

21(91.3) |

2(8.7) |

23 |

||

|

Total |

192(49.4) |

197(50.6) |

389 |

|

|

|

I have had physiotherapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all |

115(38.5) |

184(61.5) |

299 |

62.155 |

<0.001 |

|

Low level |

45(80.4) |

11(19.6) |

56 |

||

|

Moderately |

23(95.8) |

1(4.2) |

24 |

||

|

Highly |

7(87.5) |

1(12.5) |

8 |

||

|

Very highly |

1(100.0) |

0(0.0) |

1 |

||

|

Total |

191(49.2) |

197(50.8) |

388 |

|

|

|

I had health education about obstetric fistula |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all |

42(21.2) |

156(78.8) |

198 |

144.598 |

<0.001 |

|

Low level |

35(67.3) |

17(32.7) |

52 |

||

|

Moderately |

33(61.1) |

21(38.9) |

54 |

||

|

Highly |

52(92.9) |

4(7.1) |

56 |

||

|

Very highly |

29(100.0) |

0(0.0) |

29 |

||

|

Total |

191(49.1) |

198(50.9) |

389 |

|

|

|

My needs have been assessed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all |

114(38.5) |

182(61.5) |

296 |

58.011 |

<0.001 |

|

Low level |

49(79.0) |

13(21.0) |

62 |

||

|

Moderately |

20(87.0) |

3(13.0) |

23 |

||

|

Highly |

6(100.0) |

0(0.0) |

6 |

||

|

Very highly |

3(100.0) |

0(0.0) |

3 |

||

|

Total |

192(49.2) |

198(50.8) |

390 |

|

|

|

My needs have been taken care of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all |

137(42.2) |

188(57.8) |

325 |

40.612 |

<0.001 |

|

Low level |

31(83.8) |

6(16.2) |

37 |

||

|

Moderately |

18(90.0) |

2(10.0) |

20 |

||

|

Highly |

3(75.0) |

1(25.0) |

4 |

||

|

Very highly |

2(100.0) |

0(0.0) |

2 |

||

|

Total |

191(49.2) |

197(50.8) |

388 |

|

|

Accordingly, among the 215 participants who had not at all been empowered, 132 (61.4%) had not had the fistula repaired compared to 83 (38.6%) whose fistula had been repaired. Among the patients who had been highly empowered (6), a larger proportion; 4 (66.7%) had had their fistula repaired. The same applies to those who had been very highly empowered (2) whereby all of them (100%) had had the fistula repaired. This implied that there was a difference in the extent to which the obstetric fistula patients in different repair categories had been empowered to take part in decision with a significant P-value of <0.001.

Regarding daily earning, 215 indicated that they did not earn at all on a daily basis. Of these, 142 (64.4%) had not had the fistula repaired compared to 79 (35.6%) whose fistula had been repaired. Among the patients who earned highly on a daily basis (6), a larger proportion; 5 (83.3%) had had their fistula repaired. The same applied to the 1 patient (100%), who mentioned that she earned very highly on a daily basis whose fistula had been repaired. This also implies a significant difference in the extent of daily earning among obstetric patients in different repair categories with a significant P-value of <0.001.

In relation to having received aid to startup an income generating activity, findings indicated that 211 participants had not received any aid to startup an income generating activity. Of these, 138 (65.7%) had not had the fistula repaired compared to 72 (34.0%) whose fistula had been repaired. Among the patients who said that they had been highly aided to start up an income generating activity (12), a larger proportion; 11 (91.7%) had had fistula repair. The same applied to the 2 patients (100%) who had been very highly aided to startup income generating activities whose fistula has been repaired. This indicated a wide difference among the obstetric patients in different repair categories as far as receiving aid to startup an income generating activity was concerned with a significant P-value of <0.001.

Regarding skills training, 235 indicated that they had not at all received skills training. Of these, 156 (66.4%) had not had the fistula repaired compared to 79 (33.6%) whose fistula had been repaired. Among the 22 respondents who said that they had highly had skills training, 18 (81.8%) had had fistula repair. The same trend was observed among the 7 respondents who had been very highly trained in skills with all of them (100%) having had the fistula repaired. This showed a wide difference in the extent of skills training among the obstetric patients in different repair categories with a significant value of <0.001.

Concerning counseling, 195 indicated that they had not at all received counseling. Of these, 165 (84.6%) had not had the fistula repaired compared to 30 (15.4%) whose fistula had been repaired. Among the 48 respondents who said that they had been highly counseled, 46 (95.8%) had had fistula repair. The same trend was noted among 23 respondents who had been very highly counseled with 21 (91.3%) having had the fistula repaired compared to 2 (8.7%) who had not yet had fistula repair. This also indicated a significant difference in the extent of receiving counseling among obstetric fistula patients in different repair categories with a significant P-value of <0.001.

Regarding physiotherapy, 299 indicated that they had not had physiotherapy at all. Of these, 184 (61.5%) had not had the fistula repaired compared to 155 (38.5%) whose fistula had been repaired. A total of 8 respondents had been highly involved in physiotherapy of which 7 (87.5%) had had fistula repair compared to the only 1 (12.5%) respondent whose fistula had not been repaired. The same applied to the 1 respondent (100%) who had been very highly involved in physiotherapy having had the fistula repaired. A wide difference was noted in the extent of involvement in physiotherapy among obstetric fistula patients in different repair categories with a significant P-value of <0.001.

In addition, 198 had not had health education regarding obstetric fistula at all. Of these, 156 (78.8%) had not had the fistula repaired compared to 42 (21.2%) whose fistula had been repaired. A total of 56 respondents had been highly involved in health education about their condition of which 52 (92.9%) had had fistula repair compared to 4 (7.1%) respondents whose fistula had not been repaired. The same trend was observed among 29 respondents who had been very highly involved in health education, all of whom (100%) had had the fistula repaired. This implied a wide difference in the extent of involvement in health education among the obstetric fistula patients in different repair categories with a significant P-value of <0.001.

With regards to needs assessment, 296 indicated that their needs had not been assessed at all. Among whom 182 (61.5%) had not had the fistula repaired compared to 144 (38.5%) whose fistula had been repaired. A total of 6 respondents had had their needs highly assessed, 100% of whom had had fistula repair. The same applied to the 3 respondents whose needs had been very highly assessed, 100% of whom had had the fistula repaired. A wide difference was noted in the extent of needs assessment among the obstetric fistula patients in different repair categories with a significant P-value of <0.001.

With regards to whether their needs had been taken care of, 325 respondents had not at all. Of these, 188 (57.8%) had not had the fistula repaired compared to 137 (42.2%) whose fistula had been repaired. A total of 4 respondents had had their need highly taken care of and among them 3 (75.0%) had had fistula repair compared to the 1 (25%) respondent whose fistula had not been repaired. Only 2 respondents had had their needs very highly attended to, 100% of whom had the fistula repaired. A wide difference was registered in the extent to which the needs of obstetric fistula patients in the different repair categories had been addressed with a significant P-value of <0.001.

Qualitatively, the key informants highlighted counseling, physiotherapy, community mobilization, referral through the health care system, advocacy by civil society organizations and fistula ambassadors, seasonal camps and peer counseling as major social rehabilitation strategies that have been employed. The hospital staff involved in fistula management said: “We have been hosting camps where patients meet and share experiences, they listen to testimonies and peer counseling from repaired patients, are diagnosed and treated. We have also been training them in tailoring, hair dressing, weaving and knitting skills”, P 2: K2 - 2:15, a surgeon. Another one key informant who was a nurse added that,“We repair fistula, counsel patients, train them in various skills, hold camps where they interact with other patients and survivors”, P 3: K3 - 3:15. Then the desk officer also stated that,“After they have been repaired, we counsel them, train them in various skills and give them startup kits and transport”, P 5: K5 - 5:15. The partners who were also part of the key informant interviewees noted that community mobilization by Non-Governmental Organisations and churches was done. All the six partners mentioned relatively similar themes which included: counseling, skills training and health education. They indicated how patients’ hope and self-confidence increased on meeting others with the same condition in the camps.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate a wide disparity in the extent of engagement in social rehabilitation services among patients in different repair categories across all the variables with a significant value of <0.001. Quantitatively, the majority of unrepaired patients were not empowered, did not earn on a daily basis, had not received aid to startup an income generating activity, had not had skills training, counseling, physiotherapy, health education, their needs assessed and taken care of. In the qualitative study, a number of patients and key informants highlighted repair of fistula as the most significant step towards social rehabilitation. They noted that they had some degree of skills but felt incapacitated due to limited social interaction before repair.

The limited social interaction among obstetric fistula patients was associated with the physical and the psychosocial challenges they face.18,19,20 They suffer abuse of all forms, lose trust, respect and decision making power. Besides the effect of obstetric fistula on social interactions, it also affects productivity. Consequently, they feel more of an economic burden to those taking care of them.1 A patient in Mutambara et al, (2013)’s study in Zimbabwe noted how she felt so much of a burden to her family and wished she could die and have them relieved.21 Again, those taking care of them also find them burdening. This is noted in a report on the road to recovery by UNFPA, 2015 in Bangladesh which stated that whenever obstetric fistula patients are abandoned by their spouses, they return to their parents’ homes where they are seen as a burden.13 Even finding a place to stay, get medical care and network is not easy among survivors.5 Their daily earning has been noted to be low by a number of studies. A study by Barageine et al. (2014) noted that fistula was more common among women who did not earn an income such as housewives and peasant farmers.22 Women with obstetric fistula are commonly unemployable and less productive, hence they earn very little, if they did.23 According to Emasu et al, 2019, they earned less than US $ 2 per day which was generally little to meet their needs.5

Support to startup income generating activities is noted in a study in Ethiopia by Donnelly, 2015, where churches fundraised to empower the patients economically.19 In a study by Emasu in Uganda in 2019, patients indicated a need for ongoing financial support as most of them are marginalised and may not easily find a job after repair.5 Many studies indicate counseling and health education after surgery as common practices in health facilities and in community based organisations engaged in maternal health services and social rehabilitation.24,25 TERREWODE among other organisations has partnered with health institutions that repair obstetric fistula patients to ensure they are rehabilitated and reintegrated in Uganda.15 A study done in Ghana by Jarvis, et al. in 2017 noted that patients were counseled for emotional stability and health education was given to raise self-awareness especially about their bodies, to rebuild self-esteem and how they could prevent complications post-surgery. In Lombards’ review study in 2015, counseling, and health education were key recommendations.1

In relation to this study, very few patients in both repair categories had been highly involved in physiotherapy. Of the 198 participants with unrepaired fistula, 197 responded to the question on physiotherapy. Among these, only one had been highly involved. Physiotherapy is key for restoration of pelvic muscle strength and reduction in residual stress incontinence. However, it has not received the attention it deserves by researchers and in the management of obstetric fistula.26 Studies also note that needs’assessment should be individualised.27 In addition, the patients should receive group counseling and health education.1,5,28 These should cover job tailored skills training, and training in primary health care, human rights and justice, as well as economic support.5 Emphasis on hygiene, perseverance, and increased access to treatment and follow-up should be incorporated in the training curriculum.1 There should be responsiveness to women’s needs after repair, and women should keep in close contact with the health care system.8 However, all the discussed studies addressed and highlighted the challenges among obstetric fistula patients and those discussing social rehabilitation concentrated on rehabilitation post-repair. There was inadequate literature to backup the extent of involvement in social rehabilitation among obstetric fistula patients in different repair categories which this study contributed.

Conclusions

A larger proportion of patients with unrepaired fistula had not been involved in social rehabilitation activities compared to those whose fistula had repaired. Not very patients who had had fistula repair had been rehabilitated. Patients indicated a need for repair before they could be rehabilitated because those who had various skills still felt incapacitated. The study recommends the construction of more repair and rehabilitation centers and their adequate facilitation for the patients to receive the services they desire for effective social rehabilitation.

Conflicts of interests

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

The study received funding from African Development Bank through African Union Commission.

References

- Lombard L, Jenna de St. Jorre, Geddes R, et al. Rehabilitation experiences after obstetric fistula repair: Systematic review of qualitative studies. Trop Med and Int Health.2015; 20(5): 554- 568. Doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12469.

- Ahmed S, Holtz AS. Social and economic consequences of obstetric fistula: Life changing forever? International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2007; 99: S10-S15.

- World Health Organization. Obstetric Fistula, Guiding principles for clinical management and programme development. Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Child Birth. WHO. 2006. ISBN:9241593679.

- Changole J, Thorsen CV, Kafulafula U. “I am a person but I am not a person”: Experiences of women living with obstetric fistula in central region of Malawi. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2017; 17: 433. Doi 10.1186/s12884-017-1604-1.

- Emasu A, Ruder B, Wall LL, et al. Reintegration of needs of young women following genitourinary fistula surgery in Uganda. International Urogynecology Journal. 2019; 30 (7): 1101-1110. Doi: 10.1007/s00192-019-03896-y.

- Baker Z, Bach R, Ben B, et al. Barriers to obstetric fistula treatment in low income countries: A systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2017; Aug 22(8): 938 – 959.

- Bomboka JB, N-Mboowa MG, Nakilembe J. Post- effects of obstetric fistula in Uganda; a case study of fistula survivors in Kitovu mission hospital (Masaka), Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2019; 696. Doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7023-7.

- El Ayadi MA , Barageine JK, Korn A, et al. Trajectories of women’s physical and psychosocial health following obstetric fistula repair in Uganda, A Longitudinal Study. Trop Med Int Health. 2019; 24(1):53-64. DOI: 10.1111/tmi.13178.

- Atuhaire S, Ojengbede OA, Mugisha JF, et al. Social reintegration and rehabilitation of obstetric fistula patients before and after repair in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. NJOG 2018; 24 (1):5-14 Doi.org/10.3126/njog.v13i2.21714.

- Ministry of Health Report. Uganda commemorates fistula day 2016. Ministry of Health-Republic of Uganda. 2018a.

- Ministry of Health Press Statement. Press statement on International Fistula Day 2018. Department of Clinical and Community Services. Ministry of Health Republic of Uganda. May 21, 2018b.

- McCurdie KF, Moffatt J, Jones K. Vesicovaginal fistula in Uganda. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2018; 38 (6): 822-827.

- UNFPA. Obstetric fistula: The road to recovery – and respect. Dhaka, Bangladesh. UNFPA. 2015.

- Fistula Care Plus. Uganda. USAID/Fistula Care Plus/Engender Health. 2017.

- TERREWODE. TERREWODE fistula treatment and reintegration center project proposal brief. TERREWODE. 2013.

- Wang H, Chow S-C. Sample calculation for comparing proportions. Wiley Encyclopedia of Clinical Trials. 2007.

- Carpenter J, Barnes D, Dickinson C. Making a modern mental health care workforce: Evaluation of the Birmingham. University Interpersonal Training Programme in Community Mental Health 1998-2002, Durham Center of Applied Social Studies, University of Durham. 2003.

- Mselle LT, Evjen-Olsen B, Marie MK, et al. “Hoping for a normal life again: Reintegration after fistula repair in rural Tanzania. Women Health. J. Obstet and Gynaecol Can. 2012; 34(10): 927-938. Doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35406-8.

- Donnelly K, Oliveras E, Tilahun Y, et al. Quality of life of Ethiopian women after fistula repair: Implications on rehabilitation and social reintegration policy and programming. Culture Health and Sexuality. 2015; Vol. 15. No. 2, 150- 164.

- United Nations Population Fund. End the shame, end isolation, end fistula. Concept note: Partnership with the private sector foundation in Uganda in the campaign to end fistula. UNFPA Uganda. 2011

- Mutambara J, Maunganidze L, Muchichwa P. Towards promotion of maternal health: The psychological impact of obstetric fistula on women in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Asian Social Sciences. 2013; 3: 229-239.

- Barageine KJ, Tumwesigye MN, Byamugisha KJ, et al. Risk Factors for Obstetric Fistula in Western Uganda: A Case Control Study. PLOS ONE. 2014; 9 (11) e11229.

- Wall LL, Arrowsmith SD, Briggs ND, et al. The obstetric Vesicovaginal Fistula in the developing world. 2004. Committee 20

- Jarvis K, Richter S, Vallianators H. Exploring the needs and challenges of women reintegrating after obstetric fistula repair in Northern Ghana. PubMed Central. Midwifery 2017; 50: 55-61.

- Wilson SM, Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, et al. Psychological Symptoms Among Obstetric Fistula Patients Compared to Gynecology Outpatients in Tanzania. Int J Behav Med. 2015; 22(5): 605-13. Doi: 10.1007/s12529-015-9466-2.

- Castille Y-J, Avocetien C, Zaongo D, et al. One year follow-up of women who participated in physiotherapy and Health Education programme before and after obstetric fistula surgery. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2015; 128: 264-266.

- Ojengbede AO. Prevention of Vesico Vaginal Fistula and Reintegration after a Successful Repair. University College Hospital Ibadan. Scientific presentation. 2017; 1.41.

- Shittu SO, Ojengbede AO, Walla HIL. A review of post-operative care for obstetric fistulas in Nigeria. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2007; 99 Suppl 1: S79- S84 Doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.014.